De La Pena Diary

The De La Peña Diary: La Rebelión de Tejas, a Memoir by an officer of Santa Anna

(Huberman, Hugetz, & Wolf, 2000)

The De La Peña Diary (mp4)

Looking for History in The De La Peña Diary

Commentary by Dr. William Nowak

Associate Professor, Arts & Humanities

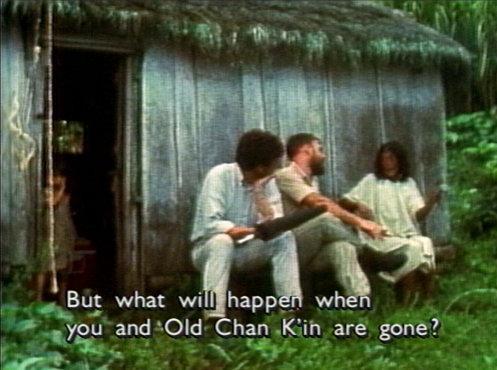

In their documentary The De La Peña Diary: La Rebelión de Tejas, a Memoir by an officer of Santa Anna (2000), filmmakers Brian Huberman, Ed Hugetz and Cynthia Wolf begin where all stories that deal with Texas history start, in the heart of Mexico. Against a backdrop of images that recall classic film visualizations of Mexican identity, a voice-over drawn from José Enrique De La Peña’s memoir of the Texas Rebellion announces this project’s main message: hay que tener mucho cuidado, porque es muy difícil ser historiador (‘be very careful because it is very difficult to be an historian’). De La Peña’s first-person account of the war was written for a Mexican audience in order to set the record straight. It was his attempt to lay blame for his nation’s defeat in the north at the feet of leaders like Santa Anna, who tried their best to silence him and his writing’s version of Mexican national history. But this film’s opening sequence and the other segments of the film that follow it suggest just how contentious a site the very concept of ‘history’ turns out to be. As excerpts from the memoir continue in voice-over and the imagery shifts to scenes shot in Texas itself, we hear a sentence about the battle of the Alamo that reports the capture and execution of Davy Crocket following the battle. With a jarring fade to black, the documentary’s straightforward explanation of this memoir and its account of the Texas Rebellion from the perspective of Mexican history suddenly seems to veer off course into an often bemusing and sometimes infuriating debate among Texas historians and other figures over the authenticity of De La Peña’s diary.

This editing of the documentary by Hugetz and Huberman forms a key aspect of the film’s

approach to historiography and documentary-making. They purposely twist the film’s

structure away from a transparent presentation of the contents of the memoir and towards

the contentious battle that it has inspired in Texas and across the US. Rather than

chronological unities or coherent historical narrative, the film presents us a series

of segments in part to demonstrate the validity of De La Peña’s warning about the

difficulties of being an historian. But they also do this to suggest the inevitable

play of chance and happenstance and sheer human messiness that creates our understandings

of the past. Besides exposing the discursive rhetoric of history, the film also offers

us a wonderfully colorful cast of characters, the passionate amateurs, the Texas movers

and shakers and the academics, who intervene in the debate over the document’s authenticity

and who take an active role in the hullabaloo that arises over its provenance and

ownership. The particulars of the diary’s past and current ownership may seem inconsequential

to ‘objective history,’ but even when achieved under the solemn academic auspices

of UT-Austin and its wealthy benefactors, the desire to control this bit of Texas

history reveals another difficulty of history: the essential and inescapable humanity

of those who, like these filmmakers themselves, endeavor to portray the truth about

our history.

This editing of the documentary by Hugetz and Huberman forms a key aspect of the film’s

approach to historiography and documentary-making. They purposely twist the film’s

structure away from a transparent presentation of the contents of the memoir and towards

the contentious battle that it has inspired in Texas and across the US. Rather than

chronological unities or coherent historical narrative, the film presents us a series

of segments in part to demonstrate the validity of De La Peña’s warning about the

difficulties of being an historian. But they also do this to suggest the inevitable

play of chance and happenstance and sheer human messiness that creates our understandings

of the past. Besides exposing the discursive rhetoric of history, the film also offers

us a wonderfully colorful cast of characters, the passionate amateurs, the Texas movers

and shakers and the academics, who intervene in the debate over the document’s authenticity

and who take an active role in the hullabaloo that arises over its provenance and

ownership. The particulars of the diary’s past and current ownership may seem inconsequential

to ‘objective history,’ but even when achieved under the solemn academic auspices

of UT-Austin and its wealthy benefactors, the desire to control this bit of Texas

history reveals another difficulty of history: the essential and inescapable humanity

of those who, like these filmmakers themselves, endeavor to portray the truth about

our history.